Court adds new hurdles for BC oil sands pipeline as separate lawsuit calls for emergency orca protections

Ocean, Shipping Comments Off on Court adds new hurdles for BC oil sands pipeline as separate lawsuit calls for emergency orca protectionsOver the past decade, plans for a big expansion of the Trans Mountain pipeline in British Columbia have garnered pushback from ocean advocates. In late 2016, the plan gained its final approval from the Canadian government (see AEI coverage), but in late August, a Federal Appeals Court overturned that approval, citing the government’s failure to assess the effects of increased shipping on the dwindling orca population and shortcomings in consultations with First Nations.

Chief Bob Chamberlin, vice president of the Union of British Columbia Indian Chiefs, called the ruling “a major win with impacts that will be felt across the country….Our wild salmon and the orcas that they support are critically under threat. The increased tanker traffic that the … project proposes is entirely unacceptable.”

However, Jonathan Wilkinson, the Minister of Fisheries and Oceans, remains confident that the court’s concerns can be addressed. While acknowledging that the government is still being guided by the courts about what level of consultation with First Nations is required, he was confident that the concerns about orca populations have been addressed by the government’s “very robust” Whales Action Plan, which includes limits on the chinook salmon fishery, ship-slowing measures, and moving shipping lanes somewhat further away from key orca feeding areas, saying that “the work the court was looking for has already been done.”

Wilkinson stresses that the increased tanker traffic—350 tankers per year, or 700 transits—is a modest addition to the 3500 other large vessels (container ships and ferries) that ply the waters of this region; he notes that “If we are going to recover the southern resident killer whale, we need to take action that will mitigate noise from all of those sources, not simply six or seven tankers coming out of the terminal every week.”

Still, “they have a lot of work to do now to see if there are ways to lessen or avoid those impacts under the Species at Risk Act,” said Misty Macduffee, a biologist with the Rainforest Conservation Foundation. “The Salish Sea is already too noisy for killer whales, so any traffic you add to it makes a bad situation worse.”

Given the precarious state of the local resident population, you can be sure that government regulators will have their feet held to the fire as this longtime controversy continues. The government has not yet announced whether it will appeal the recent ruling to the Supreme Court, or send the concerns back to the National Energy Board to address the shortcomings highlighted by the Appeals Court.

Indeed, less than a week after the Appeals Court decision, and on the very same day, the government proposed an expansion of orca critical habitat, while a consortium of environmental groups filed suit in an attempt to force the government to issue emergency protections in the face of the orcas’ ongoing population declines.

“Emergency orders are specifically designed for circumstances like this, when you have a species that needs more than delayed plans and half-measures to survive and recover,” Christianne Wilhelmson, executive director of the Georgia Strait Alliance, said in a written statement. Last year, the previous

“I have to say, personally, I was very disappointed in the action that was taken by the environmental organizations,” said Wilkinson, the fisheries and ocean minister.“They were the ones who initially asked to convene the multi-stakeholder forum. They effectively attended one meeting and then decided that they would pursue a more adversarial approach rather than a collaborative approach.”

Wilhelmson said the groups were prepared to work with government. “But the process that they set up was all about talking, not about action,” she said. “It was clear that this was just another process that was going to take months and months and months — and the orcas don’t have that.”

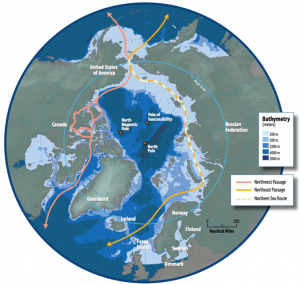

With the retreat of sea ice, both the Northwest Passage (along Canada’s northern coast) and the Northern Sea Route (along Russia’s northern coast) are seeing increases in commercial and fishing vessel traffic. While the first

With the retreat of sea ice, both the Northwest Passage (along Canada’s northern coast) and the Northern Sea Route (along Russia’s northern coast) are seeing increases in commercial and fishing vessel traffic. While the first