AEI lay summary of:

Resonate Acoustics. Macarthur Wind Farm Infrasound & Low Frequency Noise: Operational Monitoring Results. 18 July 2013. Author: Tom Evans. Client: AGL Energy Limited. Download report here.

A new report from Australia is being touted as the latest definitive proof that infrasound around wind farms is no louder than infrasound from wind and human activity in areas with no wind farms. While providing a relatively robust new set of data, the study design leaves some important questions raised by wind farm neighbors and other acousticians unanswered.

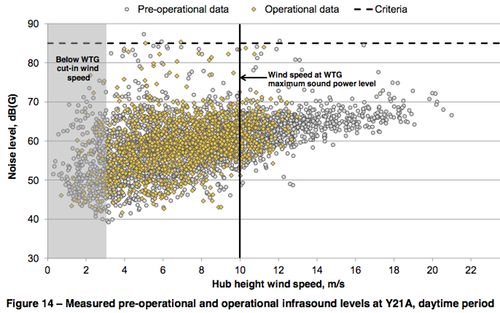

This may be the most comprehensive infrasound/low-frequency study released yet: it includes several days of measurements made prior to construction of the wind farm, along with at least ten days of measurements made when the wind farm was partly operational, and ten more days once the wind farm was fully operational. Sound was measured down to 0.8Hz, lower than some similar studies. Most importantly, sound was recorded inside the homes, which were1.8km (1.1mi) and 2.7km (2.7mi) from the nearest turbines, on opposite sides of the wind farm; at both homes, there were many more turbines at slightly greater distances than the closest ones.

At the more distant home, daytime infrasound levels prior to construction were commonly 60-70dBG, with a few peaks of 80-90dBG (grey circles below); these measurements capture the natural ambient infrasound levels caused by the wind itself, along with contributions from machinery and vehicles in the area (the threshold for human perception is about 95dBG for pure tones, perhaps lower for pulsing sounds). The peaks were much lower at night than during the day, only reaching 70dB at the highest wind speeds. With the wind farm operating (yellow diamonds below), the range of results was generally similar. Note that the operational data is not all turbine noise; some periods will have peak sound levels caused by the same local ambient sounds captured in the pre-operational monitoring period.

(dBG weighting accentuates 10-30Hz, the threshold between audible low-frequency sound and infrasound, and includes 2Hz-70Hz)

At the closer home, a limited pre-operational monitoring period only captured wind from a couple of directions, so the report’s operational results only consider periods with these two wind directions, as well. (An appendix includes the full dataset of the operational period, which closely resembles that of the more distant home shown above, though peak sounds remain below 80dBG). In the limited dataset, pre-operational levels were significantly lower, clustered between 40-60dBG. After construction, the bulk of measurements were in the same range, though there was a clear increase in periods with measurements of 60-70db, with a few peaks up to 75dB. The authors of the report suggest that some of these higher measurements appear to be due to a transient non-turbine source (one chunk of them all occurred in one short period during which wind speed and direction did not change), and much of the rest may reflect higher daytime wind-related sound, rather than turbine sound, since the limited pre-operational period did not capture much data at high wind speeds. They also note that, regardless of the source, even these peaks were within the range recorded at the more distant site pre-operation, so they reflect sound “no greater than levels that occurred naturally in the local environment (prior to the) operation of the wind farm.”

A separate section of the report addresses audible low-frequency noise, using the dBA-lf metric (dBA weighting, applied only to sound from 10-160Hz), and also reported as linear (unweighted) results at each frequency band (down to 10Hz when compared to regulatory criteria, and to 0.8Hz in a series of charts of median levels in each frequency band). Again, results showed compliance with regulatory thresholds, except for a few 10-minute periods (roughly 2% of the periods); the authors of the report consider it likely that most of these are extraneous sounds, or would be in compliance if found to be steady, rather than variable, sounds.

(Ed. note: It must be mentioned that the authors of the report are exceptionally diligent in suggesting plausible alternatives to turbine noise for each of the occasions where operational sounds appear to be higher than pre-operational; on-site human monitoring would allow at least some of these ambiguous time periods to be more definitively characterized.)

This report offers some good, solid new data, collected over a relatively long period of time (10 days or so, rather than a single day) with a decent range of wind directions and with raw data collected down to below 1Hz. While affirming that infrasound remains well below the 95dBG human perceptual threshold and 85dBG regulatory threshold, and also generally below the frequency-band limits widely applied to low frequency noise (10-160Hz), a few limitations in the research design leave several key questions unexplored:

First, the houses used in the study were relatively far away from the wind farm. While there are some noise complaints at the distances studied (especially in Australia and New Zealand), the vast majority of neighbor complaints occur when turbines are closer, from a quarter to half mile especially, and out to three-quarters of a mile (a bit over 1km) with some regularity. This study takes the important step of recording inside sound levels, but with many complaints coming at half or quarter the distance of even the closer home here (and a tenth the distance of the further home), we are left without a clear idea of infrasound or low-frequency noise levels at such locations. This may be especially relevant to the low-frequency findings, since even at the greater distances, inside low frequency sound was much closer to regulatory limits than were infrasound levels.

Second, the primary data is presented as 10-minute average sound levels. In an attempt to consider whether they were missing important shorter-term variation, the researchers also looked at 1-minute averages, and for part of the data, 10-second averages. They found that the 10-second averages closely tracked the 10-minute averages, with a similar amount of variation. However, several acousticians have suggest that the negative effects reported by some neighbors are caused by much shorter pulses of low-frequency or infrasound: investigations have centered on the roughly once-per-second blade-pass frequency, and on even more rapid fluctuations that can only be captured when filtering sound at at time frames of 10 milliseconds, matching the sensitivity of human hearing. It’s very likely that the 1-second peaks would show higher peak levels than the 10-second averages and 10-minute averages; one such analysis found 1-second peaks of 5-8dB higher than 10-second averages, with variations of up to 30dBG or more around the average when measured at 10ms, leading to peaks 10-17dB higher than the ten-second average. While regulatory criteria rely on longer averaging times, human responses to much shorter-term peaks, and/or to short and long-term variability, may well underlie many of the more vehement complaints that occur even when turbines are meeting regulatory noise limits. Investigating this possibility more widely would help settle what is becoming a central question in community responses to wind farms.

Finally, even ten days of monitoring may well not capture conditions that are particularly troublesome for neighbors. No indication is offered as to whether the monitoring was scheduled with any consideration for “worst-case” noise conditions, especially times of high atmospheric turbulence, or seasons when complaints have been highest (operational monitoring took place in southern hemisphere summer and autumn). The report notes just one two-day period when the resident at one of the homes noted that the noise seemed particularly bothersome (results those nights were generally clustered within the typical scatter of data, though on the high side of the range).

While it may appear to some that these final points are nit-picking attempts to find any small reason to ignore the overall findings of this study, I offer them not so much as critique, but rather as a nudge to researchers, to dig deep enough to more definitively address some of the particular qualities of wind turbine noise that are being hypothesized as contributors to community responses to turbines. In particular, averaging times for noise analysis must be well below one second (eg 125ms, or one-eighth of a second) in order to capture the amplitude modulation that gives many turbines their distinctive pulsing or throbbing sound quality.

This study does a good job at assessing the wind farm’s infrasound and low-frequency sounds against the regulatory criteria; however, with community complaints being common even around projects in compliance, there’s a need for research that can help clarify whether wind turbine sound does—or does not—have unusual qualities or variability patterns that existing regulatory standards are not designed to address.

In the first town-wide vote on the question of what to do about noise issues around two town-owned turbines, Falmouth voters overwhelmingly defeated a measure that would have authorized the Selectmen to continue on their preferred path of dismantling the turbines. The proposal carried a likely pricetag of about $800 per household, spread over ten years, largely to pay back loans and renewable energy credits that the town received in advance in order to buy and install the turbines. The measure fell by a 2-1 margin, with about 40% of the town’s registered voters turning out.

In the first town-wide vote on the question of what to do about noise issues around two town-owned turbines, Falmouth voters overwhelmingly defeated a measure that would have authorized the Selectmen to continue on their preferred path of dismantling the turbines. The proposal carried a likely pricetag of about $800 per household, spread over ten years, largely to pay back loans and renewable energy credits that the town received in advance in order to buy and install the turbines. The measure fell by a 2-1 margin, with about 40% of the town’s registered voters turning out. Since last fall, 105 formal complaints have been filed, by 23 different individuals living near the Sheffield, Lowell, or Georgia Mountain wind projects. Annette Smith of Vermonters for a Clean Environment is also collecting confidential complaints, some from people who have filed formal complaints, and some from neighbors who have felt it to be futile to complain to the turbine operators and/or state.

Since last fall, 105 formal complaints have been filed, by 23 different individuals living near the Sheffield, Lowell, or Georgia Mountain wind projects. Annette Smith of Vermonters for a Clean Environment is also collecting confidential complaints, some from people who have filed formal complaints, and some from neighbors who have felt it to be futile to complain to the turbine operators and/or state.  The two town-owned turbines had been projected to create a net revenue of several hundred thousand dollars a year, in electricity saved at the town Wastewater Treatment Plant, electricity sold on the open market, and Renewable Energy Credits. However, for the past year, since state DEP noise monitoring found noise levels exceeding state limits in the nearby neighborhood at night, the turbines have been shut down at night, and so operating at a deficit of about $100,000 a year due to the significantly diminished output. This

The two town-owned turbines had been projected to create a net revenue of several hundred thousand dollars a year, in electricity saved at the town Wastewater Treatment Plant, electricity sold on the open market, and Renewable Energy Credits. However, for the past year, since state DEP noise monitoring found noise levels exceeding state limits in the nearby neighborhood at night, the turbines have been shut down at night, and so operating at a deficit of about $100,000 a year due to the significantly diminished output. This  A environmental planning Tribunal in Victoria, Australia recently completed 28 days of hearings about a proposed new wind farm above the Trawool Valley. In a recent

A environmental planning Tribunal in Victoria, Australia recently completed 28 days of hearings about a proposed new wind farm above the Trawool Valley. In a recent  Watching the decade-long struggle in Massachusetts to build Cape Wind, the nation’s first offshore wind farm, researchers and state officials in Maine have chosen a different path: they decided to tackle the engineering challenges of building turbines that can float in deep water far offshore, rather than the social challenges of building wind farms in shallow water close to shore (which use fundamentally the same foundation designs as onshore turbines). Floating deepwater turbines can take advantage of even stronger, more consistent winds than their nearshore counterparts; along most of the east coast, offshore wind is far more reliable than onshore locations.

Watching the decade-long struggle in Massachusetts to build Cape Wind, the nation’s first offshore wind farm, researchers and state officials in Maine have chosen a different path: they decided to tackle the engineering challenges of building turbines that can float in deep water far offshore, rather than the social challenges of building wind farms in shallow water close to shore (which use fundamentally the same foundation designs as onshore turbines). Floating deepwater turbines can take advantage of even stronger, more consistent winds than their nearshore counterparts; along most of the east coast, offshore wind is far more reliable than onshore locations. Even before meetings began, facilitators of the multi-stakeholder group convened in Falmouth to address widespread neighborhood complaints about noise from two town-owned turbines realized that the original goal of having group develop a consensus recommendation was too high a bar to aim for. So, the process was dubbed the “Wind Turbines Options Analysis Process,” with a hope of being able to present two or three options to the Selectmen for consideration before this spring’s Town Meeting.

Even before meetings began, facilitators of the multi-stakeholder group convened in Falmouth to address widespread neighborhood complaints about noise from two town-owned turbines realized that the original goal of having group develop a consensus recommendation was too high a bar to aim for. So, the process was dubbed the “Wind Turbines Options Analysis Process,” with a hope of being able to present two or three options to the Selectmen for consideration before this spring’s Town Meeting.