In October, 2005, the Navy released the first of their sonar-inclusive EIS’s, a Draft Environmental Impact Statement covering plans for a 500 square mile Undersea Warfare Training Range (USWTR), primarily for up to 480 anti-submarine mid-frequency active sonar exercises per year, including 100 ship-based events (2/week on average, lasting 3-4 hours each). This may serve to concentrate sonar training (i.e., less sonar training on other Navy ranges, since the USWTR will have installed instruments that improve assessment of the trainings and monitor for marine life), though planning continues for sonar training in all Navy ranges. The Navy considered USWTR sites off the coasts of North Carolina, South Carolina, Maryland, and Florida, and in June 2009, released a final EIS, proposing an area off Jacksonville as the site of the USWTR.

This site has raised some concerns from environmentalists and the State of Florida, as it lies offshore from critical habitat used by the Northern right whale as winter calving grounds; less than 400 whales remain and the health of every individual is important to population recovery. The critical habitat extends to 15-20 miles from shore, with the USWTR beginning 50 miles from shore. The EIS includes several measures meant to minimize impacts on right whales; these protection measures mostly involve slowing ships and posting extra lookouts to avoid ship strikes. The Navy continues to refine its impacts modeling, incorporating new research including studies of population distribution and the effects of noise. The bottom line for now is that the Navy expects that 100,000 dolphins and over 2000 other whales will hear and change some behavior in response to sonar sounds each year (they suggest, with some justification, that these numbers–based on averaging population distributions–are likely to be over-estimates).

While most of the Navy’s assumptions and analyses are on fairly solid ground, a key one is more questionable: the assumption that few right whales will hear or react to sounds from the training ground. The Navy’s own propagation estimates suggest noise levels within the critical habitat will reach levels that have often triggered behavioral disruption in whales. It’s important that the Navy be pushed to do careful monitoring of the whales once the range is operational, and if they’ve underestimated impacts, they may need to minimize or avoid training in the winter, when the whales are nearby.

Four types of sonar training will take place in the USWTR, with the vast majority of animal impacts occurring during training scenarios involving one or more ships (rather than those deploying sonars into the water from aircraft). As noted above, these ship-based exercises will take place twice a week on average; aircraft-based sonar exercises, which the Navy predicts will impact far fewer animals, will take place roughly 30 times per month (The EIS does not clarify why the dipping sonars are expected to cause less impact; it may be that these exercises are less wide-ranging so affect a much smaller area. It is also not clear whether aircraft noise is taken into account.) In total, the EIS estimates that about 1700 marine mammals will experience temporary hearing loss each year, along with 106,000 behavioral harassments likely to occur annually, including 47 Northern right whales.

It must be stressed that harassment estimates are generated using very coarse population analyses, in which the known regional population is assumed to be spread equally across their range, whereas of course the animals tend to be concentrated into groups at any given time. This modeling approach can either over-estimate overall impacts (as every area of ocean is assumed to include some proportion of the population, whereas it is entirely possible that the training area is relatively free of animals much of the time) or underestimate actual impacts of a particular exercise (since the concentration of animals when present in a given area is likely to be higher than the models estimate). In addition, all harassment estimates are prior to any mitigation measures, which consist primarily of relatively small safety zones in which sonar would be powered down when whales are seen. The numbers of TTS may thus be significantly over-estimated, especially for dolphins and large baleen whales which are easy to see on the surface, though the longer-range behavioral impacts are likely not dramatically inflated. In the case of the Northern right whales of particular concern in this area, the Navy attempted to be conservative in its estimates: they started with the maximum number of animals likely to be present in the nearby critical habitat, then imagined them spread uniformly across the nearby continental shelf rather than concentrating in the near-shore critical habitat where they are most often seen. Thus the estimates assume whales will be present in the range’s deeper-water areas where they are, in fact, unlikely to occur.

Bearing these caveats in mind, almost all predicted behavioral harassments involve various species of dolphin, the most numerous marine mammals in these waters, though some species of larger whales are also expected to be affected. In addition to the right whales noted above, along with 108 humpback whales, the Navy estimates that 28 beaked whales, 1834 Pilot whales, and 163 Pygmy and Dwarf Sperm Whales will be have their behavior changed by sonar sounds (these are deep-diving species with some apparent sensitivity to sonar impacts). Given the regional populations of these species, the Navy holds that the behavioral disruptions will pose no significant long-term harm. While the beaked and pygmy/dwarf sperm whale numbers suggest less than 1% of regional population will be affected, the pilot whale figures are less soothing: over 40% of the population is estimated to be affected (more likely is that a smaller proportion will be affected several times each). While the factors that lead to stranding are still not clearly understood, recent research suggests that the deep-diving species may flee sonar signals at relatively moderate levels (perhaps mistaking them for predatory orcas, or simply avoiding the extremely coarse and annoying sound), and while fleeing, cause internal injuries because of unnatural dive patterns.

Source: NWTRC DEIS, p. 3.9-72

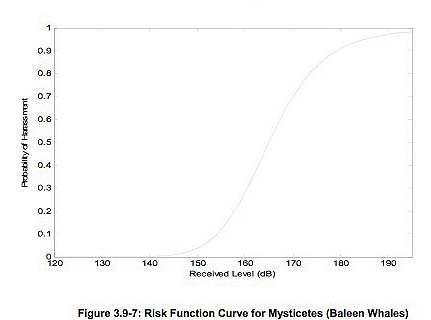

The key aspect of the Navy’s analysis that may be notably weak is the “risk function” curve that NOAA suggested be used to estimate the proportion of animals likely to show a behavioral reaction at increasing distances. While this approach is a clear improvement over earlier “step function” models which simply assumed all animals exposed at over a given threshold (often 165 or 175dB) would be affected, while none would respond at lower levels, the current model is open to question as well. It nominally accounts for some proportion of the population to respond down to 120dB, with half the population changing some behavior at 165dB, and nearly all at 195dB. The basic principle is sound, as there are many studies showing behavioral changes (sometimes dramatic, sometimes in many animals) at 120-140dB, from a wide variety of sound sources . However, the curve used in the function is extraordinarily steep, so that it becomes more an expanded step function around 165dB: virtually no animals are counted as responding below 145dB. The logic used to assign this curve’s steepness is odd: NOAA bases a slightly less steep curve for mysticetes (gray, right, humpback, and other baleen whales) on a key study that showed that 4 of 5 right whales significantly changed their behavior when exposed to sounds of 133-148dB (these were not sonar signals, but NOAA and the Navy used them because they were of similar frequency and duration) . However, even as they based the change on this study, they declined to match the curve to the data, and instead just slightly tweaked the curve, with no clear explanation of how or why they used this specific change factor. For more detail on this key aspect, which affects all the sonar training range EIS’s, see AEI’s Ocean Noise 2008 overview report. This issue is especially relevant for the USWTR, because of winter critical habitat for the Northern right whale that lies in a band extending to 15-20 miles from shore (i.e., 30-60 miles from the range). The Navy’s own propagation estimates suggest that sound levels from sonar exercises will regularly reach 130-143dB (SPL) at such distances; the steep curve allows them to assume virtually no whales within the critical habitat will react to these sounds (the curve suggests that only 1% of a population will respond to levels under 140dB; past studies of behavioral changes show a wide range of responses at these sound levels, from no change to very noticeable movement and feeding changes, but even given the uncertainty, 1% is a very low figure to use). If in fact more whales than this do respond to such noise levels, the twice-weekly ship-based sonar exercises and 7x/week aircraft-based sonar exercises may have a larger effect than they’ve accounted for (note: these weekly numbers are averages; actual training patterns are likely to be more concentrated at some times, though the Navy has explicitly refused to minimize training during the months the whales are nearby). Even a modest 10-20% of the population responding to the sounds could affect individual health, especially if young whales are more affected. A key summation of behavioral responses at different sound levels published in late 2007 suggests that baleen whales often are sensitive to these lower sound levels (again, for more detail on this study, see AEI’s Ocean Noise 2008 report).

For more details on the Navy EIS, see:

Navy USWTR EIS page, especially Chapters 4 and 6

August 13th, 2009 at 6:01 pm

I don’t know what the allowable SEL now is (if this has been fixed yet), for when powerdown or shutdown occurs, but I’m guessing it’s at around 195 microPa squared-sec. If you compare it to the curve, and the exposure is only 1 sec., then you have a near 100% chance of harassment. Why does the Navy need the chances of harassment to be near 100% for them to take (minimal mitigative) action??? Is this what we do with other laws meant to safeguard wildlife? Certainly we don’t do this with humans. If we had to be absolutely certain something harassed us before any modification of behavior was called for, nothing would be regulated at all.

January 29th, 2010 at 11:13 am

[…] the Navy released its final EIS in July (see AEI summary), including its proposed operational and mitigation measures to protect whales, it became clear […]