Whale earwax ties 150 years of stress changes to whaling, wars, and climate

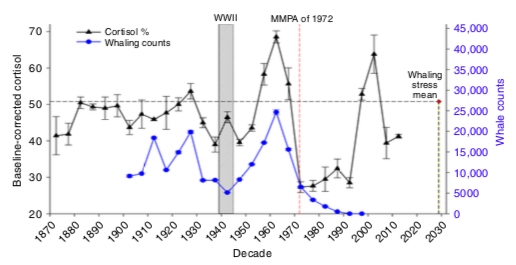

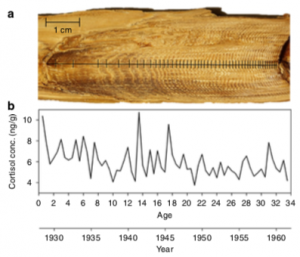

Ocean, Science Comments Off on Whale earwax ties 150 years of stress changes to whaling, wars, and climateA fascinating new study sheds light on changing stress levels in baleen whales over the course of the past 150 years. Earwax from fin, humpback, and blue whales accumulates over their lifetimes, a bit like tree rings, and the researchers were able to track cortisol levels by sampling the layers in earwax plugs from museum collections. This study averaged the results from 20 whales; the researchers are now beginning their analysis of over a hundred new samples.

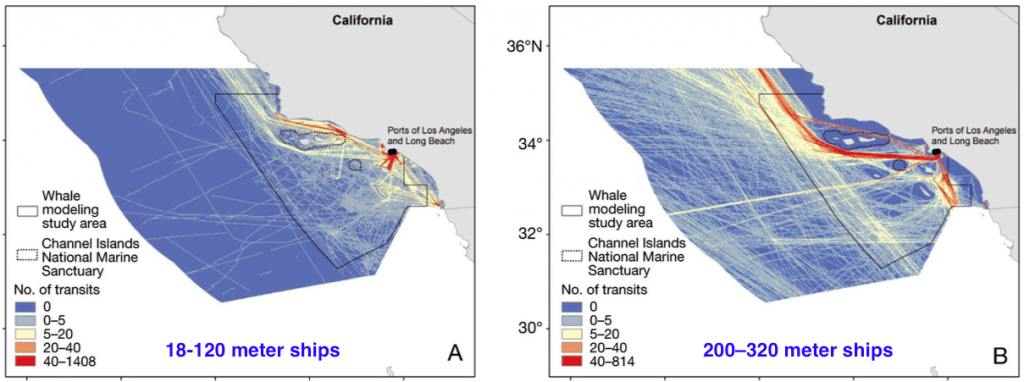

The takeaway is pretty striking: stress levels track well with increasing whaling activity through the early and mid 20th century (blue line below), and dropped dramatically when commercial whaling ended. In the midst of that span, a lull in whaling was countered by military actions durring WWII, which seems associated with a smaller spike in stress. And while stress remained low from the 70s through the 90s, it appears to be rising again in the past couple of decades; the researchers suggest that rising sea temperatures are the most closely associated factor in this recent spike, with other anthropogenic factors including shipping noise also likely contributing.

A couple of caveats are in order. Most importantly, this study had only 6 earwax samples that extended past the year 2000, so recent trends may be distorted by the small sample size; the spike in 1995-2000 represents just four whales, and the final plot points include two fin whales that lived only a couple of years (interestingly, their stress loads were low, so the recent dip may be particularly uncertain).

Not surprisingly, there were notable differences between species and a marked variability over the course of individual whales’ lives that did not track with global trends in nearly so striking a way. Here is a particular whale that suggests increased stress in particular years (including a possible WWII encounter), but which appears less affected by the global whaling trends, perhaps reflecting where it lived:

All this is really quite exciting, though. We can look forward to much more robust results as this sort of analysis is expanded to more whales, and to other hormonal markers. It’s also possible that as samples from whales that died more recently are included, regional trends related to increased shipping noise may begin to become apparent. At the same time, this is a good reminder that as much as we like to focus on acoustic factors, the stressors affecting modern whale populations are many, with climate and prey availability being especially pronounced.

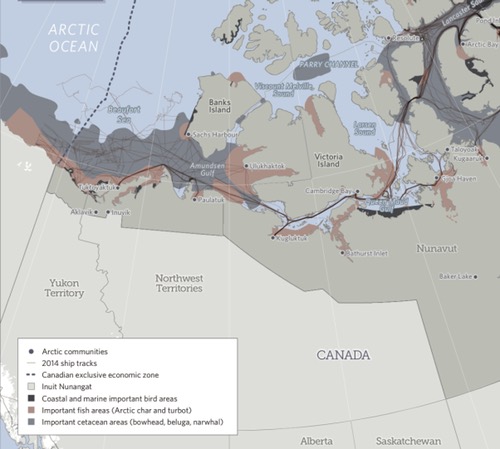

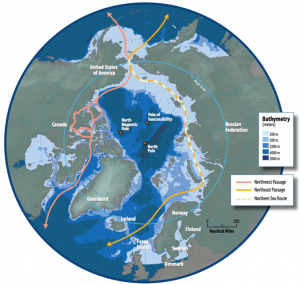

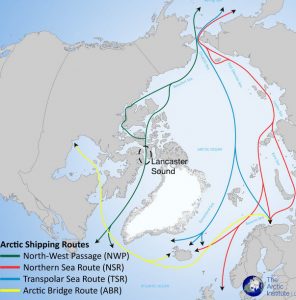

With the retreat of sea ice, both the Northwest Passage (along Canada’s northern coast) and the Northern Sea Route (along Russia’s northern coast) are seeing increases in commercial and fishing vessel traffic. While the first

With the retreat of sea ice, both the Northwest Passage (along Canada’s northern coast) and the Northern Sea Route (along Russia’s northern coast) are seeing increases in commercial and fishing vessel traffic. While the first

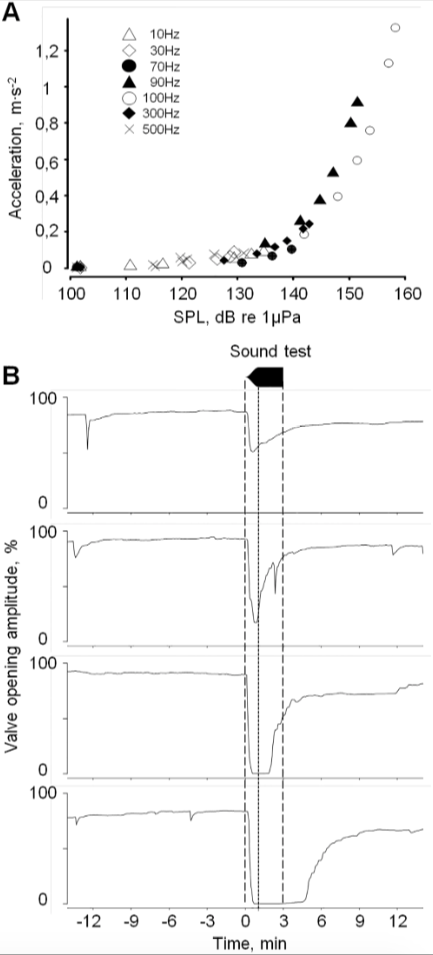

The Leighton and Hauton study, using sound playbacks mimicking a ship at 100 yards and wind farm construction at 60 yards, found that both lobsters and clams changed their digging behaviors, and triggered changes in their overall activity level (lobsters increased, clams decreased); they found no marked effects on brittlestar activity.

The Leighton and Hauton study, using sound playbacks mimicking a ship at 100 yards and wind farm construction at 60 yards, found that both lobsters and clams changed their digging behaviors, and triggered changes in their overall activity level (lobsters increased, clams decreased); they found no marked effects on brittlestar activity. They look small, about the size of a “cherry bomb” firecracker. They’re legal, exempt from the Marine Mammal Protection Act thanks to their functional purpose: protecting fishermen’s nets from seals and cetaceans poaching their catches, including squid, anchovies, and tuna.

They look small, about the size of a “cherry bomb” firecracker. They’re legal, exempt from the Marine Mammal Protection Act thanks to their functional purpose: protecting fishermen’s nets from seals and cetaceans poaching their catches, including squid, anchovies, and tuna. The so-called Northern Sea Route (or Northeast Passage) will benefit from Russia’s fleet of forty icebreakers and eleven Arctic ports; by contrast, there are no Arctic ports on the US/Canadian coastline (one deep in Hudson Bay closed last year). Rob Heubert, a former member of Canada’s Polar Commission,

The so-called Northern Sea Route (or Northeast Passage) will benefit from Russia’s fleet of forty icebreakers and eleven Arctic ports; by contrast, there are no Arctic ports on the US/Canadian coastline (one deep in Hudson Bay closed last year). Rob Heubert, a former member of Canada’s Polar Commission,  The recent

The recent

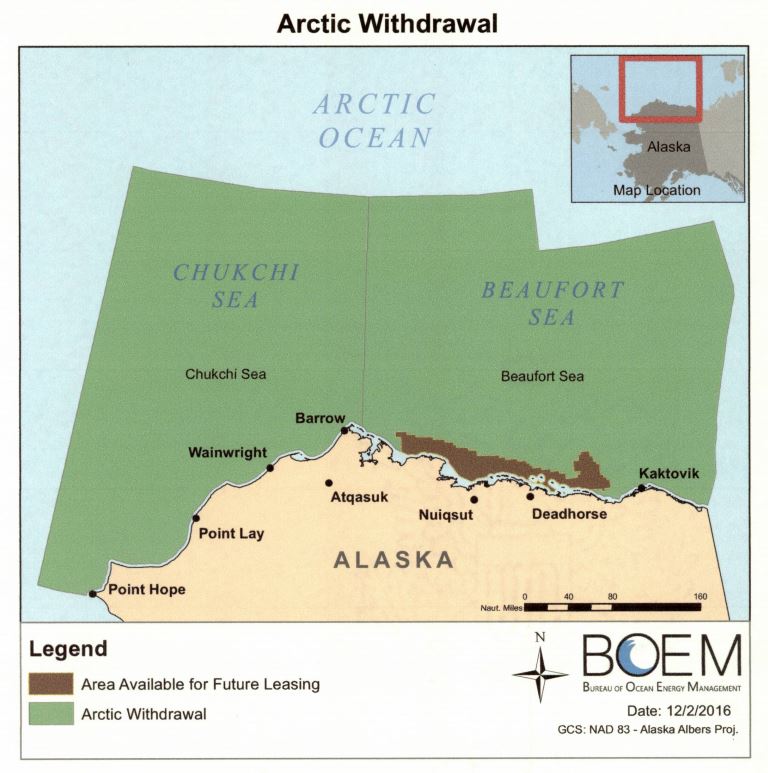

In yet another unforeseen consequence of global warming, scientists have begun charting the extent of a new underwater sound channel in the Beaufort Sea north of Alaska. As

In yet another unforeseen consequence of global warming, scientists have begun charting the extent of a new underwater sound channel in the Beaufort Sea north of Alaska. As

The biggest

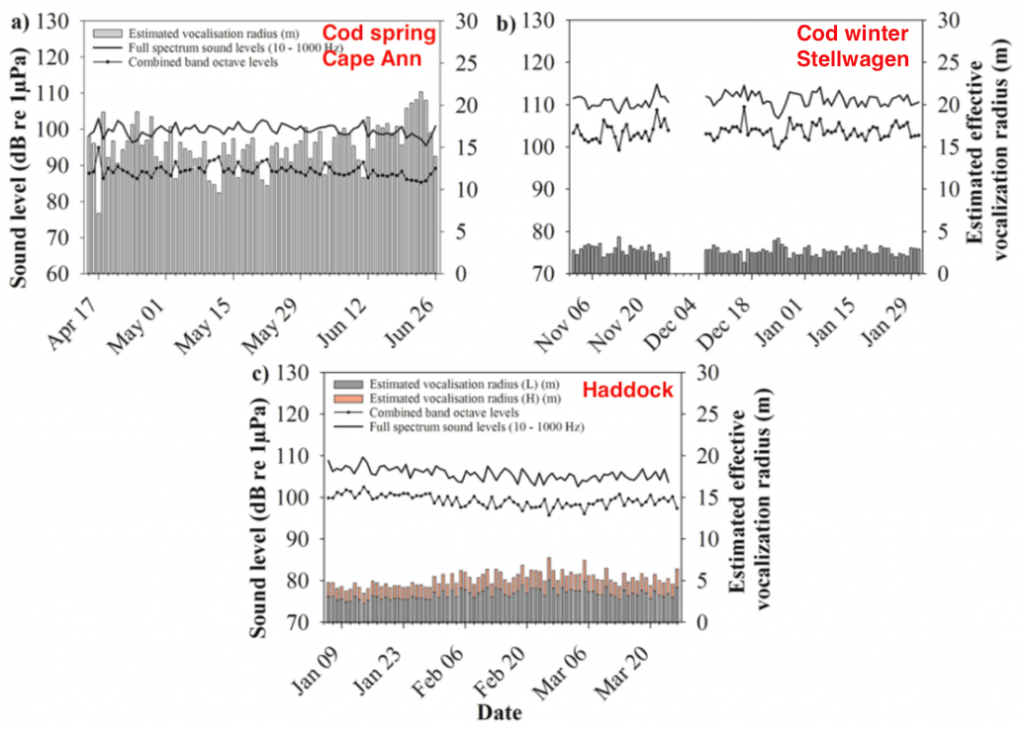

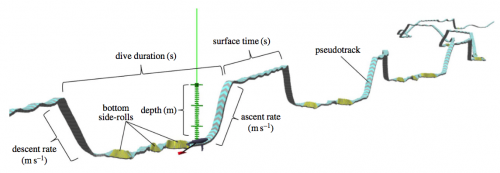

The biggest  A new study looks for the first time at the impact of human noise on an important type of humpback whale foraging activity, bottom-feeding on sand lance. The research took place in the Stellwagen Bank National Marine Sanctuary in the southern Gulf of Maine, where humpback whales routinely do deep dives at night, rolling to their sides when they reach the bottom to forage for the small fish.

A new study looks for the first time at the impact of human noise on an important type of humpback whale foraging activity, bottom-feeding on sand lance. The research took place in the Stellwagen Bank National Marine Sanctuary in the southern Gulf of Maine, where humpback whales routinely do deep dives at night, rolling to their sides when they reach the bottom to forage for the small fish.

This post from NRDC

This post from NRDC