Don’t get too worked up over Trump’s splashy offshore oil talk

Ocean, Ocean energy, Seismic Surveys Comments Off on Don’t get too worked up over Trump’s splashy offshore oil talkAn AEI big-picture commentary

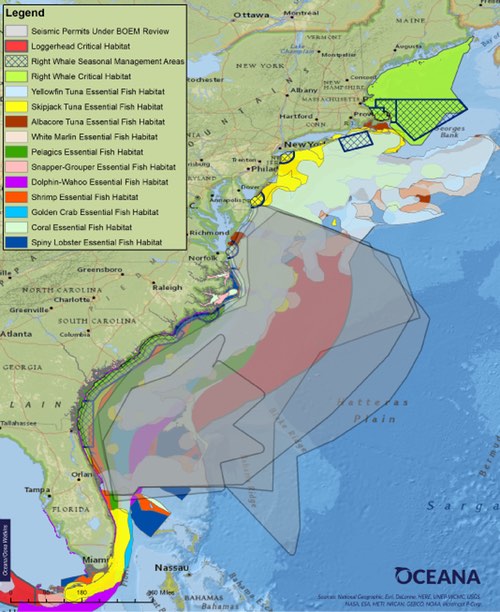

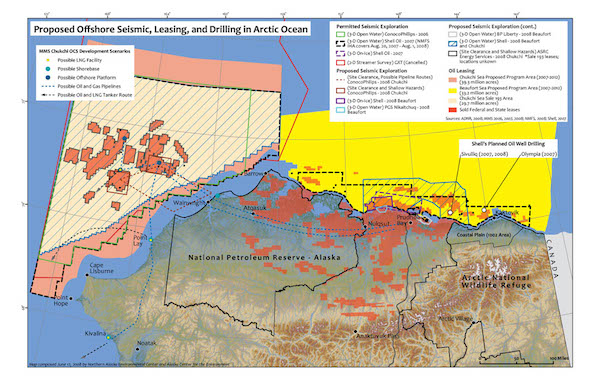

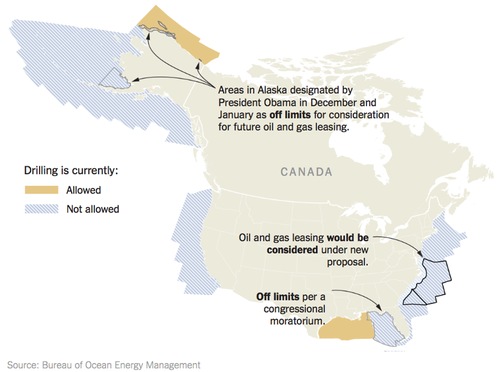

Once again, a Presidential announcement about offshore oil development has sent the media and environmental advocates into a spasm of headlines and press releases that presumes the words being uttered in DC actually reflect on-the-ground (or in this case, under-the-waves) reality. In late 2016, there was effusive praise for an effectively symbolic Obama decision to not offer leases in Alaskan and Atlantic waters (AEI’s “much ado about not much” post questioned the prevailing celebratory outburst). Fourteen months later, we’ve got a mirror-image outcry over Trump’s base-pumping proclamation about “unleashing America’s offshore oil and gas potential” through a National Outer Continental Shelf (OCS) Oil and Gas Leasing Program for the years 2019-2024.

This one sure does sound bad: opening up 90 percent of our continental shelf, with 47 lease areas including regions like New England and the Pacific Northwest that haven’t even had vague proposals for decades. Despite the boom in American oil and natural gas production that occurred during the Obama years, with much of the increased production being exported, the new administration is intent on exploiting as-yet untapped deposits, ignoring the climate imperative to leave as much oil in the ground as we can. Vincent DeVito, a Counselor for Energy Policy at the Department of Interior, practically twirls his mustache with this comment from the official DOI press release:

“By proposing to open up nearly the entire OCS for potential oil and gas exploration, the United States can advance the goal of moving from aspiring for energy independence to attaining energy dominance. This decision could bring unprecedented access to America’s extensive offshore oil and gas resources and allows us to better compete with other oil-rich nations.”

Sure, that’s just the ticket; these eager beavers can’t wait to dominate a fading industry—a decade from now, since that’s how long it takes to get offshore wells on line.

And so begins a two-year planning process that will needlessly and expensively repeat the one just completed in 2016. For we already have a National Outer Continental Shelf Oil and Gas Leasing Program, with a finalized plan set to run from 2017-2022, which the government (both federal and states), oil industry and energy consulting firms, and environmental groups spent two years and who knows how much money to complete. As always, these plans are revisited, revised, and occasionally overhauled every five years. But this gang may not be around in 2021-2022 when it’ll actually be time to once again jump into this particular vat of no-fun-for-anyone. So let’s just tear it up and do it all again now!

UPDATE, 2/16/18: Caroline Ailanthus rightfully notes that diving back into processing hundreds of thousands of public comments and writing up a new programmatic EIS will keep BOEM staff from fulfilling their many other tasks, which include assessing new science and identifying key data gaps, smaller project-level environmental assessments, and overseeing new research. She asks, “Do you suppose interfering with research in this way could be the point of this massive do-over?”

But before we get too caught up with the swarm of freaked out bees in our bonnet, let’s step back and consider the actual energy development landscape as it exists in the real world, as distinct from the fever dreams of this administration’s oil and gas cheerleaders. Read the rest of this entry »

Spurred by this article, I dug into the project’s

Spurred by this article, I dug into the project’s

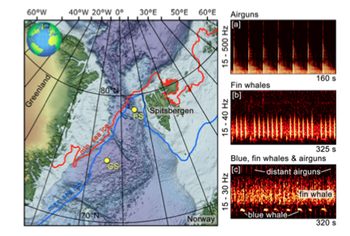

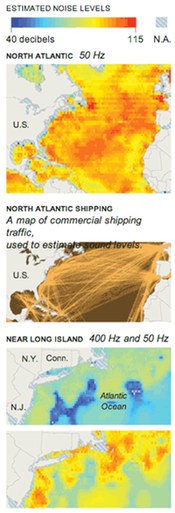

Luckily for the fin whales who are the most populous marine mammal in these remote waters east of northern Greenland, they tend to show up toward the end of the summer airgun season, and concentrate their polar activity in the winter, when the airguns go silent. But blue whales and a relatively few sperm whales like to be there in late summer, and must co-exist with the steady rumble of airgun sounds, which increase the ambient sound levels by an average of 5-10dB, and up to 20dB. By contrast, the roar of storm-driven winter waves adds up to 12dB, and the calls of thousands of fin whales add up to 10dB.

Luckily for the fin whales who are the most populous marine mammal in these remote waters east of northern Greenland, they tend to show up toward the end of the summer airgun season, and concentrate their polar activity in the winter, when the airguns go silent. But blue whales and a relatively few sperm whales like to be there in late summer, and must co-exist with the steady rumble of airgun sounds, which increase the ambient sound levels by an average of 5-10dB, and up to 20dB. By contrast, the roar of storm-driven winter waves adds up to 12dB, and the calls of thousands of fin whales add up to 10dB.

With all this in mind, Dominion Virginia Power’s first commitments to the Virginia Offshore Wind Development Authority

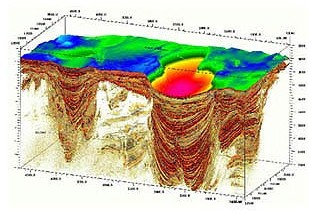

With all this in mind, Dominion Virginia Power’s first commitments to the Virginia Offshore Wind Development Authority  And, the Bureau of Ocean Energy and Management will develop new standards to assure that airgun surveys are not unnecessarily duplicative. Dozens of surveys take place every year in the Gulf, with repeat surveys sometimes needed to assess reservoir depletion, and as new and improved imaging capabilities are developed; often, survey results are considered proprietary, especially prior to bidding on leases.

And, the Bureau of Ocean Energy and Management will develop new standards to assure that airgun surveys are not unnecessarily duplicative. Dozens of surveys take place every year in the Gulf, with repeat surveys sometimes needed to assess reservoir depletion, and as new and improved imaging capabilities are developed; often, survey results are considered proprietary, especially prior to bidding on leases. “Today’s agreement is a landmark for marine mammal protection in the Gulf,” said Michael Jasny, director of NRDC’s Marine Mammal Protection Project. “For years this problem has languished, even as the threat posed by the industry’s widespread, disruptive activity has become clearer and clearer.”

“Today’s agreement is a landmark for marine mammal protection in the Gulf,” said Michael Jasny, director of NRDC’s Marine Mammal Protection Project. “For years this problem has languished, even as the threat posed by the industry’s widespread, disruptive activity has become clearer and clearer.” Watching the decade-long struggle in Massachusetts to build Cape Wind, the nation’s first offshore wind farm, researchers and state officials in Maine have chosen a different path: they decided to tackle the engineering challenges of building turbines that can float in deep water far offshore, rather than the social challenges of building wind farms in shallow water close to shore (which use fundamentally the same foundation designs as onshore turbines). Floating deepwater turbines can take advantage of even stronger, more consistent winds than their nearshore counterparts; along most of the east coast, offshore wind is far more reliable than onshore locations.

Watching the decade-long struggle in Massachusetts to build Cape Wind, the nation’s first offshore wind farm, researchers and state officials in Maine have chosen a different path: they decided to tackle the engineering challenges of building turbines that can float in deep water far offshore, rather than the social challenges of building wind farms in shallow water close to shore (which use fundamentally the same foundation designs as onshore turbines). Floating deepwater turbines can take advantage of even stronger, more consistent winds than their nearshore counterparts; along most of the east coast, offshore wind is far more reliable than onshore locations. In December, NOAA

In December, NOAA  Construction of a wind farm a bit over a mile from shore near Redcar, on the northeast coast of England, has raised the hackles of local residents. At issue is the unexpectedly loud sound of pile-driving at the site; construction of the turbine foundations entails the construction of foundations that extend 32 m (about a hundred feet) into the seabed, according to

Construction of a wind farm a bit over a mile from shore near Redcar, on the northeast coast of England, has raised the hackles of local residents. At issue is the unexpectedly loud sound of pile-driving at the site; construction of the turbine foundations entails the construction of foundations that extend 32 m (about a hundred feet) into the seabed, according to