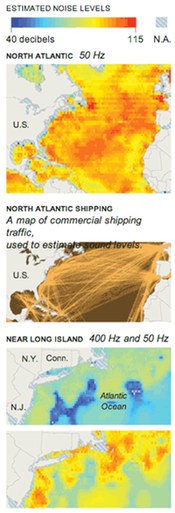

In the wake of NOAA’s large-scale ocean noise mapping project, two much more detailed studies from the Pacific Northwest have highlighted the likelihood that current shipping noise is already pushing the limits of what biologists think many ocean creatures can cope with.

In the wake of NOAA’s large-scale ocean noise mapping project, two much more detailed studies from the Pacific Northwest have highlighted the likelihood that current shipping noise is already pushing the limits of what biologists think many ocean creatures can cope with.

The first study recorded the sound from several types of boats and ships traversing Admiralty Inlet, between Whidbey Island and Port Townsend, WA, and used these recordings, correlated with ship traffic records, to model sound levels throughout the area. The Seattle Times summarizes this work, which found that at least one large vessel (container ship, ferry, or large tug) was in the area at least 90% of the time, and that the average noise level was about 120 decibels, which is the threshold above which federal agencies begin being concerned about behavioral impacts on some ocean species.

“Continuous noise at that level is considered harassment of marine mammals,” said University of Washington’s Christopher Bassett, one of the authors of the paper. “About 50 percent of the time, we even exceed that threshold.”

“It is concerning that the noise levels are so high,” said Marla Holt, a research biologist at Seattle’s Northwest Fisheries Science Center. “When you see how often this happens and how chronic the noise exposure is, that’s when you start to say, ‘Wow.'”

Interlude: Brief OrcaLab recording of threatened Northern Resident killer whales in Caamano Sound, BC, chatting with each other and then being drowned out by a cruise ship:

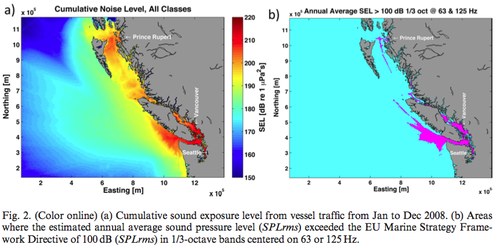

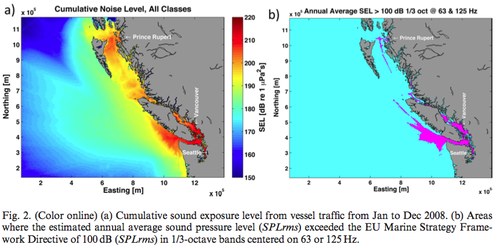

To the north, another study mapped shipping noise in the Salish Sea (south and east of Vancouver Island), and on up the British Columbia coast to the port of Prince Rupert. This work, funded by World Wildlife Fund-Canada, introduces a comprehensive approach to modeling sound transmission from ships, incorporating differences between vessel types, transmission loss in a variety of bathymetric and seabed conditions, and temperature-driven variations in sound speed during different seasons. (Download a PDF presentation summarizing the full WWF-Canada report here; a shorter version appeared in JASA in November). Here, too, large areas are subject to excessive shipping noise; the maps below show total sound levels, and the areas where the annual average of two specific low frequencies are above the 100dB threshold that the European Union considers the target for biologically sensitive areas:

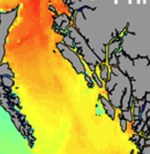

But now, check out that lighter colored patch about halfway between BC’s two big offshore islands.

That’s an inland waterway that heads up to Kitimat, the proposed site of a major new port, the Northern Gateway, which would serve as the primary port for shipping tar sands oil to Asia. An annual total 220 super-tankers would head though that currently mostly-yellow zone, all the way up that long, narrow channel that points to the upper right hand corner of this close-up (and leave again—so more than one passage a day on average). As you might imagine, there is widespread concern about the risks of accidents and spills in these often treacherous passages, but the increase in shipping noise is also being raised as a question.

That’s an inland waterway that heads up to Kitimat, the proposed site of a major new port, the Northern Gateway, which would serve as the primary port for shipping tar sands oil to Asia. An annual total 220 super-tankers would head though that currently mostly-yellow zone, all the way up that long, narrow channel that points to the upper right hand corner of this close-up (and leave again—so more than one passage a day on average). As you might imagine, there is widespread concern about the risks of accidents and spills in these often treacherous passages, but the increase in shipping noise is also being raised as a question.

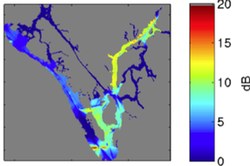

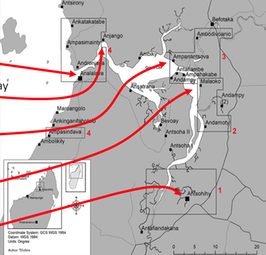

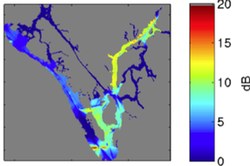

A second study by the same research team, led by Christine Erbe, took a close look at current and likely increases in shipping noise, should Northern Gateway go forward, and what they found is not reassuring. Noise levels will increase by up to 6dB in the approach lanes in Caamano Sound, and by 10-12dB in the narrow fjord into Kitimat (see map on right). In the western channel (the wider approach), where sound would likely increase 3-6dB (representing a doubling to quadrupling of sound energy), Humpbacks would hear tankers and their accompanying two tugboats for 43% of daylight hours, and orcas (due to thier higher-frequency hearing, less intruded upon by low-frequency ship noise) would hear the tankers 25% of the time. Fewer whales venture all the way up the fjords, but some would likely be present in the bend in the route, where noise levels would increase by 10dB, representing a 10-fold increase in sound energy.

A second study by the same research team, led by Christine Erbe, took a close look at current and likely increases in shipping noise, should Northern Gateway go forward, and what they found is not reassuring. Noise levels will increase by up to 6dB in the approach lanes in Caamano Sound, and by 10-12dB in the narrow fjord into Kitimat (see map on right). In the western channel (the wider approach), where sound would likely increase 3-6dB (representing a doubling to quadrupling of sound energy), Humpbacks would hear tankers and their accompanying two tugboats for 43% of daylight hours, and orcas (due to thier higher-frequency hearing, less intruded upon by low-frequency ship noise) would hear the tankers 25% of the time. Fewer whales venture all the way up the fjords, but some would likely be present in the bend in the route, where noise levels would increase by 10dB, representing a 10-fold increase in sound energy.

“There is a worry they will go away and not come back to these fiords,” says Erbe. “This is critical habitat, important to them. Are they going to be able to feed elsewhere? We can only answer that with long-term monitoring.”

These studies, one of which utilized four seasons of recordings, and the other presenting a comprehensive and verifiable sound modeling approach, both offer exciting steps forward in the study of coastal and oceanic acoustic habitats. Let’s hope that coming years produce many more studies from other regions around the world that continue to develop these innovative techniques.

Detailed Northern Gateway study: Erbe, C., Duncan, A., and Koessler, M. 2012. Modelling noise exposure statistics from current and projected shipping activity in northern British Columbia. Report submitted to WWF Canada by Curtin University, Australia.

BC sound modeling study: Erbe, C., MacGillivray, A., and Williams, R. 2012. Mapping Ocean Noise: Modelling Cumulative Acoustic Energy from Shipping in British Columbia to Inform Marine Spatial Planning. Report submitted to WWF Canada by Curtin University, Australia.

Shorter version: Erbe, C., MacGillivray, A., and Williams, R. 2012. Mapping cumulative noise from shipping to inform marine spatial planning. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 132 (5), November 2012. 423-428.

Puget Sound study: Bassett, C., Polagye, B., Holt, M., Thomson, J. 2012. A vessel noise budget for Admiralty Inlet, Puget Sound, Washington (USA). J.Acoust.Soc.Am. 132(6), December 2012

Related:

Kathy Heise and Hussein Alidina. Ocean Noise in Canada’s Pacific Workshop, January 31-February 1, 2012. Summary Report. WWF-Canada. 54pp. Read or download PDF

WWF-Canada Submission to Enbridge Northern Gateway Joint Review Panel, 9/19/12. (mostly terrestrial impacts; some ocean noise sections) Read or download PDF

Immediately after NOAA’s approval, environmental organizations

Immediately after NOAA’s approval, environmental organizations  One study is further along, having

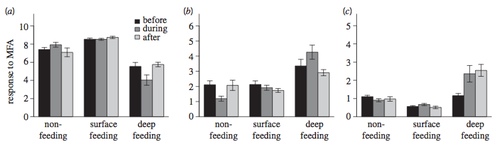

One study is further along, having  She said the sound of “bait balls” of prey, such as schools of fish, could be greatly heightened when a feeding frenzy involving larger fish and seabirds broke out. Dr Constantine said whales had been observed swimming rapidly from over a kilometre away toward prey aggregations, “so we’re very interested to find out if there are specific acoustic cues they home in on”.

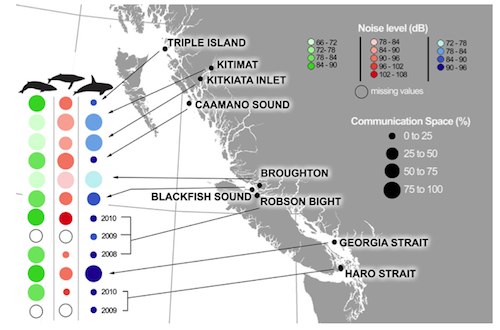

She said the sound of “bait balls” of prey, such as schools of fish, could be greatly heightened when a feeding frenzy involving larger fish and seabirds broke out. Dr Constantine said whales had been observed swimming rapidly from over a kilometre away toward prey aggregations, “so we’re very interested to find out if there are specific acoustic cues they home in on”. (noise levels and communication space in median noise conditions)

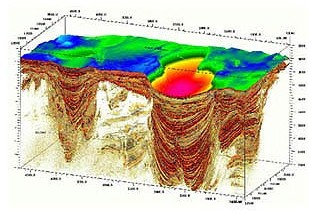

(noise levels and communication space in median noise conditions) For the first day and a half, larvae exposed to airgun noise showed significant developmental delays. At close to two days, the noise-exposed group appeared to be nearly as likely to be fully developed as the control group (upper right chart). But, after passing the 48-hour mark, as the larvae moved into the next stage of development, those in noise lagged again; at 66 hours, all of the control larvae had completed the D-veligar development, while a large proportion of those exposed to noise did not complete this transition. In addition, a significant proportion of the noise-exposed larvae began exhibiting physical abnormalities (localized bulges in the soft body of the larvae, but not in the shell). By the end of the study, at 90 hours, an average of 46% of noise-exposed larvae showed malformations, ranging from 27%-91% in the four flasks being independently analyzed. (Ed. Note: I’ve reproduced five of the seven charts here, omitting samplings at 54hrs and 90hrs for the sake of better readability.)

For the first day and a half, larvae exposed to airgun noise showed significant developmental delays. At close to two days, the noise-exposed group appeared to be nearly as likely to be fully developed as the control group (upper right chart). But, after passing the 48-hour mark, as the larvae moved into the next stage of development, those in noise lagged again; at 66 hours, all of the control larvae had completed the D-veligar development, while a large proportion of those exposed to noise did not complete this transition. In addition, a significant proportion of the noise-exposed larvae began exhibiting physical abnormalities (localized bulges in the soft body of the larvae, but not in the shell). By the end of the study, at 90 hours, an average of 46% of noise-exposed larvae showed malformations, ranging from 27%-91% in the four flasks being independently analyzed. (Ed. Note: I’ve reproduced five of the seven charts here, omitting samplings at 54hrs and 90hrs for the sake of better readability.) For the first time, a mass stranding appears to have been triggered by a relatively high-frequency mapping sonar; most previous strandings (though rare) have been associated with mid-frequency military sonars. An international, independent scientific review panel (ISRP) of five well-known marine mammal researchers has concluded that a 2008 stranding event on the northwest coast of Madagascar was likely precipitated by an avoidance response to a multi-beam echo-sounder system (MBES) being used to map the seafloor.

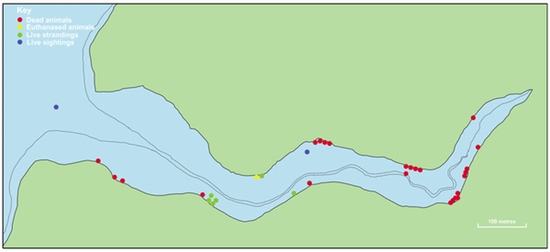

For the first time, a mass stranding appears to have been triggered by a relatively high-frequency mapping sonar; most previous strandings (though rare) have been associated with mid-frequency military sonars. An international, independent scientific review panel (ISRP) of five well-known marine mammal researchers has concluded that a 2008 stranding event on the northwest coast of Madagascar was likely precipitated by an avoidance response to a multi-beam echo-sounder system (MBES) being used to map the seafloor. Acoustic modeling suggests that the whales would have been able to hear the MBES signals for at least 30km from the survey vessel, to near the island seen on the map to the right, 25km offshore, at which point they apparently continued moving toward shore until straying into the stranding zone. Why the animals continued moving inshore after the sonar was no longer audible is unclear. This is a species that normally lives only in deep waters; once the whales moved past the cliff near the survey area and into shallow shelf waters, they may have been quite confused, and further behavioral anomalies (including ending up in the estuary) may be unrelated to the survey sounds.

Acoustic modeling suggests that the whales would have been able to hear the MBES signals for at least 30km from the survey vessel, to near the island seen on the map to the right, 25km offshore, at which point they apparently continued moving toward shore until straying into the stranding zone. Why the animals continued moving inshore after the sonar was no longer audible is unclear. This is a species that normally lives only in deep waters; once the whales moved past the cliff near the survey area and into shallow shelf waters, they may have been quite confused, and further behavioral anomalies (including ending up in the estuary) may be unrelated to the survey sounds.

And, the Bureau of Ocean Energy and Management will develop new standards to assure that airgun surveys are not unnecessarily duplicative. Dozens of surveys take place every year in the Gulf, with repeat surveys sometimes needed to assess reservoir depletion, and as new and improved imaging capabilities are developed; often, survey results are considered proprietary, especially prior to bidding on leases.

And, the Bureau of Ocean Energy and Management will develop new standards to assure that airgun surveys are not unnecessarily duplicative. Dozens of surveys take place every year in the Gulf, with repeat surveys sometimes needed to assess reservoir depletion, and as new and improved imaging capabilities are developed; often, survey results are considered proprietary, especially prior to bidding on leases. “Today’s agreement is a landmark for marine mammal protection in the Gulf,” said Michael Jasny, director of NRDC’s Marine Mammal Protection Project. “For years this problem has languished, even as the threat posed by the industry’s widespread, disruptive activity has become clearer and clearer.”

“Today’s agreement is a landmark for marine mammal protection in the Gulf,” said Michael Jasny, director of NRDC’s Marine Mammal Protection Project. “For years this problem has languished, even as the threat posed by the industry’s widespread, disruptive activity has become clearer and clearer.”

In the wake of

In the wake of

That’s an inland waterway that heads up to Kitimat, the proposed site of a major new port, the Northern Gateway, which would serve as the primary port for shipping tar sands oil to Asia. An annual total 220 super-tankers would head though that currently mostly-yellow zone, all the way up that long, narrow channel that points to the upper right hand corner of this close-up (and leave again

That’s an inland waterway that heads up to Kitimat, the proposed site of a major new port, the Northern Gateway, which would serve as the primary port for shipping tar sands oil to Asia. An annual total 220 super-tankers would head though that currently mostly-yellow zone, all the way up that long, narrow channel that points to the upper right hand corner of this close-up (and leave again A second study by the same research team, led by Christine Erbe, took a close look at current and likely increases in shipping noise, should Northern Gateway go forward, and what they found is not reassuring. Noise levels will increase by up to 6dB in the approach lanes in Caamano Sound, and by 10-12dB in the narrow fjord into Kitimat (see map on right). In the western channel (the wider approach), where sound would likely increase 3-6dB (representing a doubling to quadrupling of sound energy), Humpbacks would hear tankers and their accompanying two tugboats for 43% of daylight hours, and orcas (due to thier higher-frequency hearing, less intruded upon by low-frequency ship noise) would hear the tankers 25% of the time. Fewer whales venture all the way up the fjords, but some would likely be present in the bend in the route, where noise levels would increase by 10dB, representing a 10-fold increase in sound energy.

A second study by the same research team, led by Christine Erbe, took a close look at current and likely increases in shipping noise, should Northern Gateway go forward, and what they found is not reassuring. Noise levels will increase by up to 6dB in the approach lanes in Caamano Sound, and by 10-12dB in the narrow fjord into Kitimat (see map on right). In the western channel (the wider approach), where sound would likely increase 3-6dB (representing a doubling to quadrupling of sound energy), Humpbacks would hear tankers and their accompanying two tugboats for 43% of daylight hours, and orcas (due to thier higher-frequency hearing, less intruded upon by low-frequency ship noise) would hear the tankers 25% of the time. Fewer whales venture all the way up the fjords, but some would likely be present in the bend in the route, where noise levels would increase by 10dB, representing a 10-fold increase in sound energy. In December, NOAA

In December, NOAA  NOAA Fisheries announced on Monday that it would review the status of the southern resident population of killer whales, in response to a delisting petition from California farmers. In addition to boat noise, a decrease in salmon runs is a key driver of reduced orca populations, and protection plans for the orcas include protections for salmon, including maintaining river flows. The farmers claim this is denying them the water they need. The heart of the petition is a challenge to NOAA’s determination that this local population is genetically distinct and deserving protection, although the species as a whole is not threatened.

NOAA Fisheries announced on Monday that it would review the status of the southern resident population of killer whales, in response to a delisting petition from California farmers. In addition to boat noise, a decrease in salmon runs is a key driver of reduced orca populations, and protection plans for the orcas include protections for salmon, including maintaining river flows. The farmers claim this is denying them the water they need. The heart of the petition is a challenge to NOAA’s determination that this local population is genetically distinct and deserving protection, although the species as a whole is not threatened.