NRDC, allies mount new legal challenge to Navy sonar

Effects of Noise on Wildlife, News, Ocean, Sonar Comments Off on NRDC, allies mount new legal challenge to Navy sonar2012 is shaping up as the year when the legal battle over the US Navy’s active sonar systems ramped back up to full-scale confrontation. A 2009 agreement between NRDC and the Navy put legal challenges on the back burner – actually, entirely off the stovetop – in favor of dialogue. But recent permits issued by NOAA’s National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS) are now being attacked for the small sizes of the off-limit areas. NRDC has continued to call, in pubic and presumably in private, for the Navy to keep their sonar activity out of biologically important areas as they move forward with both low-frequency (LFAS) and mid-frequency (MFAS) active sonar deployments. This week, a new set of rules to govern LFAS was challenged in federal court on the grounds that the exclusion zones are far too limited. In January, a similar challenge was filed for existing MFAS permits issued by NMFS; see this earlier AEI coverage for details on the MFAS action.

The new suit, like the January one, differs from the initial round of sonar challenges in that the target is the NMFS permits, rather than the Navy’s operations. As you may recall, the Supreme Court ultimately ruled that Naval priorities deserved wide latitude in the interpretation and implementation of environmental laws. By challenging NMFS’s analysis of the risks and the mitigations included to protect marine wildlife, these challenges may well take a different path through the legal maze.

The new LFAS rules allow the Navy, for the first time, to operate the high-power sonars in most of the world’s oceans. The previous 5-year planning process focused on the western Pacific (in part due to the US stategic focus/concern on China and North Korea, and in part due to legal pressure during that round of planning). A previous AEI post goes into some detail on the new LFAS “letter of authorization,” which covers the first year of the 5-year period (short version: during the first year, operations will remain predominantly in the western Pacific, with a couple of operations north and south of Hawaii).

Because a single LFA source is capable of flooding thousands of square miles of ocean with intense levels of sound, the Navy and NMFS should have restricted the activity in areas around the globe of biological importance to whales and dolphins. Instead, they adopted measures that are grossly disproportionate to the scope of the plan – setting aside a mere twenty-two “Offshore Biologically Important Areas” that are literally a drop in the bucket when compared to the more than 98 million square miles of ocean (yes, that’s 50% of the surface of the planet) open to LFA deployment. The apparent belief that there are fewer than two dozen small areas throughout the world’s oceans that warrant protection from this technology is not based in reality.

NRDC also stresses that the LFAS is loud enough to remain at levels that can cause behavioral disruptions at up to 300 miles away. The Navy has said that take numbers, especially takes for injuries or death, will be low or zero once mitigation measures are implemented, though the permits allow for some of these “Level A” takes; for the first year, they are authorized to kill or injure up to 31 whales and 25 seals and sea lions.

While the

While the

In addition to three environmental organizations, the Native Village of Chickaloon is party to the lawsuit, saying that NMFS did not fulfill necessary consultation with the tribe, and noting that while the tribe is barred from its traditional hunts due to declining beluga numbers, the permits allow oil and gas development to put whales at risk.

In addition to three environmental organizations, the Native Village of Chickaloon is party to the lawsuit, saying that NMFS did not fulfill necessary consultation with the tribe, and noting that while the tribe is barred from its traditional hunts due to declining beluga numbers, the permits allow oil and gas development to put whales at risk.

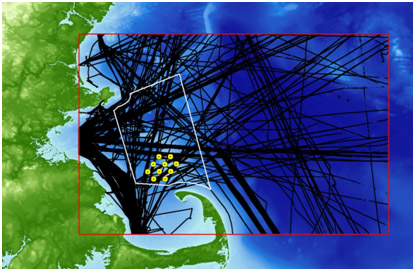

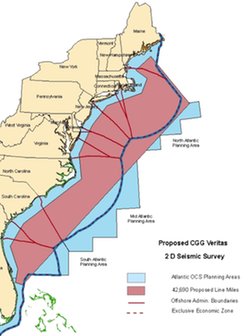

I’ve yet to dig into the PEIS to examine its alternatives or proposed mitigation measures, but a quick look at maps illustrating applications already received from oil and gas exploration companies affirms that the entire east coast could become an active seismic survey zone (the map at left is one of nine applications; there is much overlap among them).

I’ve yet to dig into the PEIS to examine its alternatives or proposed mitigation measures, but a quick look at maps illustrating applications already received from oil and gas exploration companies affirms that the entire east coast could become an active seismic survey zone (the map at left is one of nine applications; there is much overlap among them). I’ve also been invited to participate in a small, invitation-only symposium being convened by NOAA (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration) and BOEM (Bureau of Ocean Energy and Management) to gather feedback on

I’ve also been invited to participate in a small, invitation-only symposium being convened by NOAA (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration) and BOEM (Bureau of Ocean Energy and Management) to gather feedback on  A Canadian frigate used its mid-frequency active sonar this week during a training exercise in Haro Strait, north of San Juan Island and south of Vancouver Island. The sonar emissions from the HMCS Ottowa (right) were picked up by whale researchers at Beam Institute, who raised concerns about sonar use in an area designated by the US as critical habitat for orcas. You can read a detailed report from Beam, including sonograms and MP3 files of the sounds heard,

A Canadian frigate used its mid-frequency active sonar this week during a training exercise in Haro Strait, north of San Juan Island and south of Vancouver Island. The sonar emissions from the HMCS Ottowa (right) were picked up by whale researchers at Beam Institute, who raised concerns about sonar use in an area designated by the US as critical habitat for orcas. You can read a detailed report from Beam, including sonograms and MP3 files of the sounds heard,  A fascinating new study provides the first direct evidence that shipping noise may increase stress levels in whales. During the days after the World Trade Center attacks, global shipping was halted; a team of researchers studying right whales in the Bay of Fundy decided to go ahead and continue collecting fecal samples, and were struck by how peaceful it was: Rosalind Rolland

A fascinating new study provides the first direct evidence that shipping noise may increase stress levels in whales. During the days after the World Trade Center attacks, global shipping was halted; a team of researchers studying right whales in the Bay of Fundy decided to go ahead and continue collecting fecal samples, and were struck by how peaceful it was: Rosalind Rolland

Two of the US’s most widely-respected ocean bioacousticians have called for a concerted research and public policy initiative to reduce ocean noise. Christopher Clark, senior scientist and director of Cornell’s Bioacoustics Research Program, and Brandon Southall, former director of NOAA’s Ocean Acoustics Program, recently published

Two of the US’s most widely-respected ocean bioacousticians have called for a concerted research and public policy initiative to reduce ocean noise. Christopher Clark, senior scientist and director of Cornell’s Bioacoustics Research Program, and Brandon Southall, former director of NOAA’s Ocean Acoustics Program, recently published