Fish survey sounds reduce humpback songs 120 miles away?

Bioacoustics, Effects of Noise on Wildlife, Ocean, Science Add commentsAEI lay summary of the following paper:

Risch D, Corkeron PJ, Ellison WT, Van Parijs SM (2012) Changes in Humpback Whale Song Occurrence in Response to an Acoustic Source 200 km Away. PLoS ONE 7(1): e29741. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0029741

Read or download online (free)

An ongoing research project that monitors whale calls and shipping noise in Stellwagen Bank east of Boston Harbor has reported an unexpected reduction in humpback whale songs during an 11-day period in which their recorders picked up low frequency sounds from a fish-monitoring system 120 miles away. If this data does indeed represent whales ceasing singing or moving away in response to the distant sonar, this would be the first clear-cut indication that discrete human noise events may affect marine mammal behavior outside the immediate area. The authors note that these results could suggest that impact assessments need to consider effects at longer ranges, and that effects may occur at received sound levels much lower than those generally considered worthy of concern. This study simply reports the reduction in singing; any longer-term effect that may have on the animals is unknown (these are not mating calls).

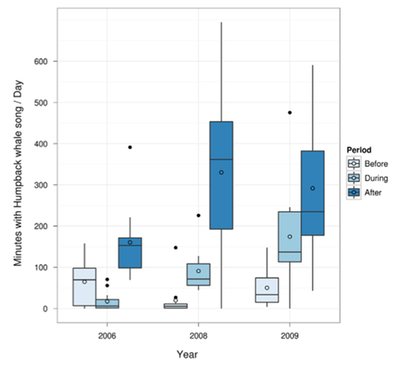

The reduction in songs occurred at a time of year (early fall) when humpback songs are beginning to increase in this area; on years when the fish sonar was not in operation, the numbers of songs steadily increased over the 33-day study period. But in 2006, when the fish sonar was heard at Stellwagen Bank for 11 days (8 of which included sonar sounds for over 7 hours), the number of minutes per day when humpbacks were singing dropped, some days to zero. The average (mean) number of hours of whale song dropped from about 75 in the previous 11 days to about 15 minutes during the time the fish sonar was heard, before increasing to close to 3 hours per day once the sonar transmissions ceased.

The figure below shows the data from each of three years. For each year, there are 33 days of data, with the middle 11 days being the period (Sept. 26-Oct 6) in which the sonar sound occurred in 2006. The open circles are the mean minutes/day for each 11-day period, with the rectangular boxes representing the upper and lower quartiles of data for each period; black dots represent one or two days in each period in which the calling rates for that day were unusually far outside the range for other days in that period.

Ed. note: Interpreting the results of vocalization studies is complicated by the fact that there is much variability in vocalizing rates, and response/sensitivity to human noise, from one animal to another; and similarly, in numbers of whales in the area from year to year. (This acoustic data counts singing minutes, but not animal numbers, which must be monitored visually.)

The year in which the sonar transmission took place could be a year in which fewer whales were present than in the other years studied, raising some questions about whether the reduction in singing could have been a reflection of relatively quiet, or sensitive, individuals in that particular year. However, the data also shows generally typical, or even slightly higher than average calling in the first 11 days of the period during 2006, relative to other years, which could also suggest that the unfamilar sound during the next 11 days reduced the vocal output of the whales, or drove them away, as reflected in the unusually low number of minutes/day of calling in the final 11-day period in 2006. Of course, other factors (such as prey abundance or weather) could be the cause of the lower call rates that year.

Of particular note is that the sonar system in question, an Ocean Acoustic Waveguide Remote Sensing (OARWS) system, creates sound in the same frequency range (400-900Hz), and time duration (around a second), as humpback songs. This may make the whales unusually responsive to these particular unusual sounds. The 415Hz OAWRS signals were most dominant, recorded in Stellwagen at around 110dB re 1uPa RMS, 22 dB above the background sound, and 12dB above the level at which 50% of whales are likely to hear it. It’s also interesting to note that the hydrophones deployed in Stellwagen can hear humpbacks only within about 18 miles, while the OARWS signals were audible from 120 miles away.

Complicating the situation is that the OAWRS system is one of several being used to make more accurate assessments of the dangerously depleted cod stocks in the Gulf of Maine (which stretches from Cape Cod north to the Canadian Maritimes); this system provides a large-scale picture of fish shoals within a 60 mile diameter area. Local fishermen are in desperate need of clear data that will indicate when cod numbers have rebounded enough to allow renewed and greater harvests, so any effort to reduce the use of these fish assessment sonars will run up against this need for better data. (See this good article from the Gloucester Times on the implications for fishermen.) It’s unclear from press coverage of this study and the cod stock issue whether there are times that the fish assessments could take place while whales are not in the region.