In-depth soundscape ecology study underway at Alaskan wildlife refuge

Effects of Noise on Wildlife, News, Science, Vehicles, Wildlands Add commentsA really fascinating multi-year study is underway at the Kenai National Wildlife Refuge which sits on a peninsula along the south side of the Cook Inlet in Alaska (Anchorage and Wasilla are at the innermost tip of Cook Inlet). Tim Mullet, a Ph.D. student at what looks like an amazing program at the Institute of Arctic Biology, is undertaking what may well be the most comprehensive soundscape analysis ever undertaken on a landscape scale. “As far as I know, nobody has attempted to model sound in the landscape,” says Mullet. “We could encounter some big surprises there.”

Over several summers and winters, he is collecting recordings with 13 units placed in different areas of the refuge; some are permanent locations, and others he moves around in order to explore the soundscape in more areas. He already has 85,000 hours of sound data, and hopes to expand his recorder array to 23 units this year as well. These two articles provide a great overview of what Tim’s up to.

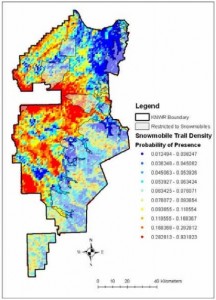

Snowmobile density in the Kenai NWR (red most, blue least); note that the shaded areas on the east side are nominally closed to snowmobile traffic, yet show some sign of activity.

“At this point, I’ve got an idea that 30 to 40 percent of Kenai’s wilderness could be affected by human–made noise,” says Mullet. The study goes beyond simple decibels (loudness), though. It is a foray into the emergent field of soundscape ecology, which examines the interplay of anthrophony (human–induced sounds) and biophony (natural sounds).

Loudness is “a piece of this study,” says Morton, “but another piece is the origin of sound—whether it’s human or nature—and developing a ratio between the two. It’s definitely cutting edge.” Understanding the relationship between anthrophony and biophony is important to the refuge and wildlife conservation in general, Morton says, because “human–generated noise can drown out natural noises—and that can be a huge deal, to the point where animals can’t actually hear themselves.”

In addition to collecting and mapping sounds, Mullet is studying whether moose who live closer to high levels of sound show higher stress levels than those in more sonically pristine areas. While some snowmobiling advocates seem concerned that Mullet’s work may lead to new restrictions on their access to the refuge, Mullet himself understands and appreciates the key role of snowmobiles in Alaskan recreation, and aims to simply clarify what the various cumulative impacts of noise may be. Snowmobile trails create other impacts as well, especially compacting snow, which can benefit wildlife by offering travel paths, though biologists are also interested in how this easier travel may shift some predator/prey relationships.

More info: See two articles written by Mullet, one on the many qualities of snow, and the other exploring our different ways of listening, and introducing the Kenai study. Also of interest from Tim is this research proposal, which summarizes previous research into both the impacts of noise and other snowmobile impacts (unfortunately, the sections of the proposal that are yellow-highlighted come through on the pdf as blocked out).