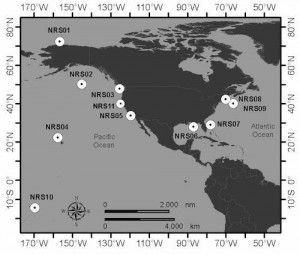

A new network of long-term acoustic monitoring stations is being deployed by NOAA-funded researchers in ocean waters from Massachusetts to the Arctic and Samoa. The Ocean Noise Reference Station (ONRS) Network represents the next step in data collection for NOAA, which has increased its focus on ocean noise in recent years.

A new network of long-term acoustic monitoring stations is being deployed by NOAA-funded researchers in ocean waters from Massachusetts to the Arctic and Samoa. The Ocean Noise Reference Station (ONRS) Network represents the next step in data collection for NOAA, which has increased its focus on ocean noise in recent years.

Agencies, researchers, and NGOs are all concerned about the effects of chronic moderate noise on whales, seals, and fish (along with crustaceans and even eggs and larvae). NOAA’s ocean noise mapping project is a big step forward, but it’s largely based on modeling of known ship and seismic survey activity. Actual recordings made at sea by various researchers serve as “ground-truthing” for these models; early indications have been that the models are pretty good, usually within 5-10dB of actual recorded levels.

The ONRS network takes acoustic monitoring another step forward by deploying identical equipment in many regions, thus collecting “consistent and comparable multi-year acoustic data sets covering all major regions of the U.S.” In addition to getting a better idea of regional differences (and consistencies), researchers will be investigating “how the ‘soundscapes’ at each of these sites changes, i.e. does it become noisier, are there more or less biological sounds, and is there a dramatic shift in the species present?” All this will feed into NOAA’s ten-year effort to develop an Ocean Noise Strategy.

The most recent deployment took place this fall at the Cordell Bank National Marine Sanctuary off the coast near San Francisco (it’s not even on the maps on the NOAA site yet, though I added it above as NRS11). The hydrophone deployment mission (right) received substantial funding from the International Fund for Animal Welfare (IFAW), along with the ongoing NOAA support for data collection and analysis. Cordell Bank is one of the richest foraging grounds for marine mammals, thanks to an upwelling of cold water that attracts a wide range of species to feed. At the same time, many of the thousands of ships traveling from Asia to ports in San Francisco Bay and further south along the California coast pass close enough that their “acoustic footprint” extends into the Sanctuary. This can, at the very least, make it harder for whales or fish to hear each other as well as they’re used to, limiting the area over which they can communicate and causing them to raise their voices. There are also indication that some species expend energy avoiding moderate noise, and that feeding and perhaps mating can be temporarily disrupted. Most pernicious may be the possibility that living in elevated noise can increase physiological stress, triggering “a suite of negative effects,” according to one of the researchers.

The most recent deployment took place this fall at the Cordell Bank National Marine Sanctuary off the coast near San Francisco (it’s not even on the maps on the NOAA site yet, though I added it above as NRS11). The hydrophone deployment mission (right) received substantial funding from the International Fund for Animal Welfare (IFAW), along with the ongoing NOAA support for data collection and analysis. Cordell Bank is one of the richest foraging grounds for marine mammals, thanks to an upwelling of cold water that attracts a wide range of species to feed. At the same time, many of the thousands of ships traveling from Asia to ports in San Francisco Bay and further south along the California coast pass close enough that their “acoustic footprint” extends into the Sanctuary. This can, at the very least, make it harder for whales or fish to hear each other as well as they’re used to, limiting the area over which they can communicate and causing them to raise their voices. There are also indication that some species expend energy avoiding moderate noise, and that feeding and perhaps mating can be temporarily disrupted. Most pernicious may be the possibility that living in elevated noise can increase physiological stress, triggering “a suite of negative effects,” according to one of the researchers.

Other research efforts are also adding to our understanding of the effects of shipping noise. In Canada, Port Metro Vancouver recently deployed a hydrophone to examine the underwater noise from container ships headed into its facilities. 3000 such vessels traverse the waters each year, along with even more ferry transits and various recreational boats. It’s part of the Port’s Enhancing Cetacean Habitat and Observation Program. One of its most interesting goals is to zero in on ships that may be unusually loud and in need of some maintenance:

The hope is to establish baseline information to track noise levels and to identify noise levels from specific ships. The results could lead to simple mitigation measures such as hull and propeller cleaning, shore-based financial incentives, and information for regulatory agencies and for naval architects to build quieter ships.

Here’s some more from the researchers on that project.

And in the Bering Sea, acoustic monitoring is providing important baseline data on marine mammal presence, which will play into any future oil and gas development, as well as the potential for global shipping to extend into Arctic regions as polar ice melts:

“This passive acoustic monitoring technique allows us to detect the presence of vocalizing marine mammals continuously — 24 hours per day — in all weather conditions, over periods of weeks to months, over distances of 20 to 30 kilometers, and is a proven sampling method in the waters offshore Alaska,” explained lead researcher Kathleen Stafford.

Meanwhile, eavesdropping went on during the summer and fall in the Gulf of Mexico, and plans are being made for a recording network all the way around Antarctica, in some of the world’s most remote and acoustically pristine waters.

We’re listening more closely and widely than we ever have—the next question will be, are we willing to actually do something with what we learn, and find ways to slow or roll back our relentless intrusion into the natural soundscapes of the oceans?