VT towns reject wind farm & town-wide personal payments

Human impacts, News, Wind turbines Add comments Two central Vermont towns have voted against plans to build a wind farm on the hills along their border, despite a late-in-the-game offer from wind developers to mitigate some of the downsides by making direct annual cash payments to residents. While landowners that host turbines always receive payments from wind developers, and some projects have included “good neighbor” payments to nearby landowners, this is the first time I know of in which a project extended a cash-payment program to include all local citizens.*

Two central Vermont towns have voted against plans to build a wind farm on the hills along their border, despite a late-in-the-game offer from wind developers to mitigate some of the downsides by making direct annual cash payments to residents. While landowners that host turbines always receive payments from wind developers, and some projects have included “good neighbor” payments to nearby landowners, this is the first time I know of in which a project extended a cash-payment program to include all local citizens.*

The votes were not close, with over 60% of voters in both towns giving thumbs-down to the wind farms. Iberdola, the developer, had pledged to respect the voters and discontinue its efforts to build there if they lost.

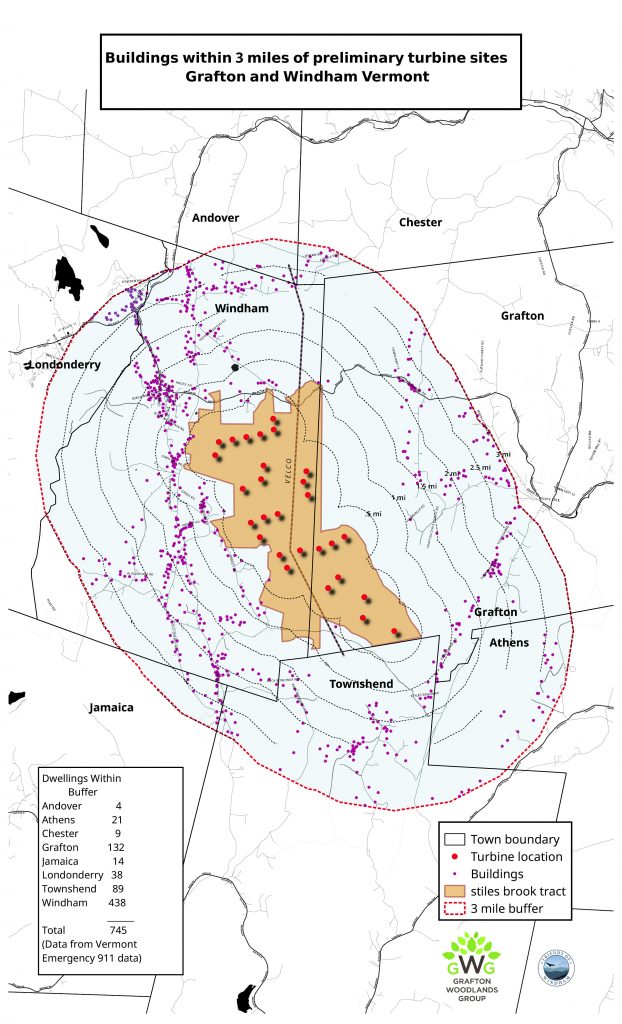

A key factor for many locals was the unusually high number of homes relatively close to the ridge where the turbines were slated to be built (click image to enlarge). As compared to two other large projects in the state (Sheffield and Lowell Mountain), this project had a concentration of homes close enough to more or less guarantee that the turbines would be easily heard regularly—over a hundred within a mile, and another 150 between a mile and a mile and a half. This increased home density (4-6x more than Sheffield or Lowell) continued out to 2 miles, where noise could be audible at times.

What to make of the payment offers?

While many locals took offense at what could easily be seen as an attempt to buy their votes, the cash payments plan was also a long overdue acknowledgement that the presence of turbines in a community does amount to a “dis-amenity,” a negative contribution to local sense of place and quality of life. For most residents, these impacts are relatively modest (a dislike of the sight or sound of turbines in the distance, or noise being only occasionally loud enough to wake or disturb them), such that modest financial payouts may feel both fair and welcome. In this case, the annual payments would have been $427 (over $10,000 through the 25-year life of the project) in Grafton and $1125 per year (over $28,000 total) in Windham, with more turbines and fewer residents. Still, for those who found the turbine noise intolerable—as some Vermont wind farm neighbors have—these payments would not do much to ease their discomfort.

One of the frustratingly difficult questions is quantifying what proportion of nearby residents have been severely impacted by existing wind farms. While ongoing formal complaints are relatively rare, usually involving one or a few homeowners per project, some undoubtedly suffer in silence; most surveys suggest a third or more who hear turbines dislike the sound at least somewhat, while half or more are unbothered. This ambiguity is the reason that it’s valid for individual towns to make differing choices about where to draw the line on wind development; Grafton and Windham made a very clear choice, even given the option of financial compensation for moderate effects.

Another Vermont wind developer recently went further in attempts to reassure neighbors who are especially worried that they may be among those most impacted. This fall, as part of its initial permit application to the Vermont Public Service Board, Swanton Wind, LLC said that it would buy the homes of anyone within 3000 feet who decides within 6 months of the wind farm becoming operational that they don’t want to live near the turbines. I would much prefer to see this sort of proactive willingness to buy out neighbors extend for at least a year, or preferably a couple years, so that residents can see how the turbine noise varies by season, and have a better chance to feel out whether they can adapt to the new noise or not; and, the 3000-foot limit is an arbitrary one, leaving much vulnerability and uncertainty for people at somewhat greater distances who will undoubtedly hear turbines at very noticeable sound levels. For many people, this sort of offer is a bitter pill to swallow—they don’t WANT to move; they just want the wind farm to not be built nearby. Yet the move toward these sorts of options for the most-impacted neighbors represents an important step within the wind industry, which continues to turn a generally deaf ear to most community concerns about wind farm noise, preferring to downplay the problem rather than face it directly.

It will take some years, and a few projects playing out these offers in the real world, to see what sorts of compensation will be both fair and acceptable to communities. At this point, concerned citizens are afraid that the impacts they encounter will be far more than money can compensate for, and see financial offers as bald-faced attempts to buy them off, while companies have much uncertainty about how many people might take them up on any good-faith offers they do put forth to try to ease the fear of worst-case scenarios, and so are keeping their offers modest to start. It will be interesting to see whether these initiatives mark the start of a more honest conversation about the wider shared costs of wind development.

*The Record Hill Wind Farm in Maine included a similarly unusual cash payment plan that was designed to reimburse local electric ratepayers for their electricity use; this approach aimed to counter the common concern that the wind-powered electricity is not directly accessible to local residents who have to live with the turbines.